A strange thing happens when you’ve been a patient for an extended period: You develop a fear of ‘letting down’ your doctors, of disappointing your medical team. Or, perhaps, this is this something unique to my situation – I’m not entirely sure. Whatever the case, it’s something my GP recognized, and called me on, shortly after I retuned home from the hospital.

I’d had an appointment booked for a few days after discharge from the hospital in July, and though I wanted nothing more than to cancel – I desperately needed a break from doctors – I kept the appointment. As I waited for my doctor to enter the intimate consultation room, questions regarding what I should say, of how I should address the coming debrief, consumed me.

So too did worries of my drastically changed appearance.

He hasn’t seen me since before the surgery, I thought. What will he think of me?

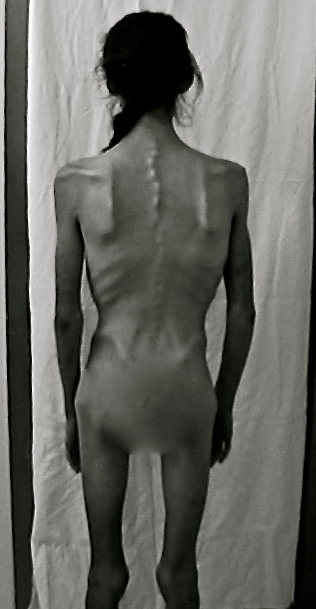

I was embarrassed by my sunken eyes, my gaunt face, frail frame; by my raspy voice, my dull complexion. Even though this doctor has seen me in far worse condition – he’s the one who initially convened what is now my entire medical team, who took me on as a patient when I first appeared before him at barely 60 pounds – I didn’t want to be seen by anyone looking as I did.

Breathe, Alheli. You’re OK.

Those automatic, comforting words echoed in my mind, bringing a sense of calm, just as they’ve done in the past.

He’s your doctor. He’s here to help you recover. You haven’t failed him.

My thoughts were interrupted by the knock signaling my doctor’s imminent arrival.

I watched intently as he initially laid eyes on me, trying to catch an unguarded, honest reaction upon seeing me in this state.

Nothing.

He smiled sympathetically and sat down, pulling his chair close to mine.

“Alheli –” he began, but before he could continue, I broke down.

Goddammit, I silently scolded myself. No. Stop it. You’re fine.

But I couldn’t stop, I wasn’t fine; The tears refused to slow. Perhaps it’s because everything was still so fresh, the experience so raw, that I could not control this reaction. I sat sobbing, describing what had happened, though my doctor was already well aware, having read the reports from the hospital.

But he wanted to hear me tell it, wanted to know what it was like from my perspective.

I apologized repeatedly for “being such a mess, such an emotional wreck.” I’d always look forward to appointments with this particular doctor because we discuss things on the same level. He doesn’t dumb anything down, is always willing to take the extra time to explain in medical terms what he thinks, what is happening, what will be done. That day, however, we could not have that conversation.

And I hated it.

“You know,” he said, “I don’t understand why you feel the need to apologize. When you come to see me I don’t expect things to be perfect, or you to be well. Don’t ever feel the need to put up a front just to please me. When something is wrong, let it be wrong in here.”

That’s the thing: I didn’t want things to be wrong. I desperately wanted things, finally, to be right. I wanted to be well.

I just wanted – want – to be normal.

I took him back to some of the moments that haunt me most, back to the time between the first and second surgery, when it was a constant flurry of procedures and tests.

There was worry evident in the eyes of my medical team as I returned from the scope, bowel perforated. After being ported for yet another CT to see the extent of the damage, I lay in absolute agony, gasping for breath in the hall as technicians readied the machine. The man who’d walk me through the test leaned over and pressed his face next to mine.

“Just hold on a little bit longer,” he whispered. “Keep fighting. Keep breathing.”

I recall the whirring of the machine; the intense injection of contrast into the veins; the subsequent warmth pooling around my throat, abdomen, pelvis, groin.

“Take a breath, and hold it in,” the machine commanded, and I complied, though it was a struggle.

I was choking just to breathe.

The scan complete, I returned to the unit and to an unspoken sense of urgency. Nurses raced to reattach my IV lines, the PCA, the oxygen, as my surgeon worked to get an OR prepped: “She’ll be in surgery as soon as possible.”

Hours passed, toxins coursed through my body.

Nurses, whom I’ve always assumed are immune to the cycle of life and death, appeared distraught. There were three who separately approached me, asking permission to pray over me before I was sent for the second, emergency surgery. Even in my semi-coherent state, I was taken aback.

This is not normal. Things are not good.

I agreed for their sake: I didn’t expect prayer to influence the outcome, but if it would bring them comfort, then why not?

I then began to wonder if, perhaps, I should be praying; Whether I should ask for protection from God, beg for my life.

But I didn’t pray.

Divine intervention isn’t going to save you, I reasoned. That’s what medical intervention is for.

Down in the OR, I’m met with the same team of residents who’d observed my first surgery; am briefed by the same anesthetist about the ‘going under’ part.

“Do you have any questions?” he asked, wheeling me into a room that was far smaller, more intimate than the one I’d encountered back in May.

“Just one,” I answered. “Am I going do die?”

He stood over me, trying to find words that would comfort, but not promise. “We’ll take good care of you.”

I don’t press him further.

When my surgeon enters, we lock eyes. Mine are filled with tears, his with resolve.

I felt a familiar burn creep up my arm as my vision began to blur. I didn’t have any final thoughts this time around; I simply closed my eyes, exhaled, and resigned myself to the fact that, this time, I might not wake up.

The following weeks, where I was in and out of consciousness, were peppered by hallucinations. One in particular was both recurring and deeply unsettling. Over and over, I’d be taken to the chapel on the main floor, dismembered, and various parts of my body placed in vaults for individual funerals. My mother was there, as was a priest whom I didn’t know, and they argued over which ceremony to give each body part.

“Perhaps a Buddhist service for the leg,” my mother would say. “Maybe a Catholic mass for the arm,” the priest would add.

Repeatedly I’d relive this experience, and it wasn’t until well after my second blood transfusion, when I was entirely conscious and aware, that I fully understood that this did not happen. I mean, I knew it didn’t happen, but my brain couldn’t quite separate the hallucination from reality in terms of feeling it.

And death — it was everywhere: There were terminal cases on my unit, Code 66s (pre-Code Blue) and Code Blues night and day. I’d hear “Baby Green Reset (resuss?)” or something to that effect, over the PA, knowing that, on another floor, an infant was coding.

One day, while having my PICC dressing changed, after having woken from yet another dismemberment hallucination, a Code 66 was called for my unit, which unleashed a rush of carts and hurried footsteps in the corridor.

“Oh my god, is that me?” I pressed the nurse. “No,” she reassured me. “If it was for you, you can bet there’d be far more activity in this room than there already is.”

Every day I’d ask my surgeon if I was going to die, and every day he’d give the same answer: “We’re doing what we can. You just keep fighting.”

Privately he told my mother that, although things appeared to be stabilizing, without an enormous effort on my part, I would not make it out of the hospital.

A nurse who I’d become quite close with quietly pleaded: “You need to fight, you cannot give up. You can’t take it easy or take it slow. This is critical. Please. Please push. Please try.”

Until then, I thought I had been trying. I didn’t understand what more she wanted or expected me to do. Perhaps she thought I’d resolved to just die? I’m not quite sure. But the desperation in her voice told me all I needed to know about my prospects. Maybe she sensed that I honestly didn’t see a way out, that I’d accepted that death just might be what was next for me, and she didn’t want me to dare entertain that thought.

Because if I did, it just might become my reality.

So I fought. Not only for myself, but for my nurses, for my surgeon. I fought for my whole medical team; I didn’t want to let them down. I didn’t want them to feel responsible if I didn’t pull through. So, if not for me, I wanted so badly to survive for them.

I didn’t want to disappoint them.

When sitting on the side of the bed, my body convulsing, and the nurse recommends we “do just one trip around the nursing station,” I say, “no. We’ll do five.”

When the dietician says to “aim to drink half of this Boost by the end of the day,” I say, “no. I’ll drink two of them.”

When my surgeon suggests I “try to start tapering off the PCA (morphine),” I stop using it altogether.

“Boy, when you decide to get better, you really get better, don’t you?” remarked one of he charge nurses.

I suppose so.

Which is why I agreed to that day pass, something my mother, bless her heart, tried to paint as a wild success, but which was, in fact, an absolute nightmare for us both.

I’d just been taken off my entire support system — the TPN, IV, PCA; no catheter, no constant vital monitoring – nothing. By the time we pulled up to the house I was in the throes of a panic attack. I couldn’t breathe, felt completely detached from reality.

“I knew if I just got you out of the car that we’d be OK,” my mom now tells me. “But I wasn’t about to go back to the hospital without you at least setting foot in the house. I needed you to do that much, to get past that anxiety.”

I did manage to leave the car, unsure of what else I could do at that point. If this was all another hallucination, which is what it felt like at that moment, then it was only a matter of time before I woke up. So I just needed to play along, just needed to go through the motions until then.

I forced myself from the car and stumbled into the house, where I faced the next big hurdle: the shower.

The first time my heart failed was back in Ontario, and it happened just after I’d stepped out of the hospital shower. I remember being incredibly short of breath while under the stream of water, of fighting for consciousness as I emerged, trying to stay alert just long enough to dress myself and make it back to my room to call the medical staff.

It’s an experience that remains etched in memory, which evokes the same panic, same sense of complete helplessness when a similar situation is encountered.

So, being not entirely lucid and in a state of extreme physical weakness, I was terrified to shower. My mind repeatedly flashed back to the night I coded and I was so afraid it would happen again.

But this time, if it happened, I wouldn’t even be in the safe confines of the hospital.

So I made my mother sit in the bathroom, phone in hand, poised alert 911 if/when I had a heart attack, as I forced myself through the mundane task of bathing. I gasped for breath between sobs and tried to concentrate on the walls, the curtain, the soap – on anything to keep the brain focused on something tangible, rather than the scene playing out in my head: The one where my throat closed up, darkness crept in, pulse faded…

Mentally, physically, emotionally spent, I returned to the hospital after four hours at home. It was hard enough to summon the strength to walk from the car to the main doors, and then to the elevators which would take me back to the 8th floor, but as I approached those sliding metal doors, I insisted on taking the stairs. Why? Because if I could climb 8 flights of stairs in this state, on the verge of collapse, then I knew I’d be able to tackle them again when less vulnerable.

Even if, on that day, at that time, your mind insists you cannot, you can think back to this moment, Alheli, and tell yourself: Yes you can.

Tell yourself: You’re OK.

I had to stop for breath four times during the brief ascent, but I did it. I made it up to the 8th floor, back to unit 83, and back to my room where I asked the nurse to take my vitals so I could record them in my mind.

You were certain you were going to die today, but you didn’t, and you won’t. Your blood pressure is fine, pulse is strong, O2 sats normal. Remember that the next time the anxiety creeps in; the next time panic takes over. This isn’t going to be easy. There will be other days just as trying a this, but you made is through this one, you’ll make it through the others.

The following day I insist my rehab walk be taken outside. I was intent on walking the kilometer loop, no matter how slow; I was done with hallway wandering. My mind (and body) were telling me I was too weak, so I had to prove them wrong. My mother accompanied me at first, and the first time I ventured out alone, I did so with the extra support of a wheelchair (pushing, not riding). Each day I’d extend the route just a little further, push the legs to work just a little harder.

In a matter of days I could feel the heart and lungs responding: the breath was less short; the heartbeat less intense, less desperate.

And suddenly, I was being discharged, for good.

Though at the time I spoke/wrote with confidence about being home, about continuing the recovery process and rebuilding all I’d lost physically over those months in hospital, I privately remained skeptical about my ability to do so.

The extended period of inactivity and complete immobility had my extremely limber body seized into a tight mass. Whereas my usual stretching routine would include various hyper-extensions, over-splits, and other contortions, I was now incapable of reaching past my knees.

My chest and abdomen formed a single concave unit; it felt as if there were ropes tied to my back at each shoulder blade, pulled forward, around my arms, and tied into a giant knot at my sternum. My deepest breath was still roughly half my actual lung capacity; the partial collapse in the left lung persisted.

I felt defeated just thinking about the daunting task ahead.

You’re fooling yourself if you think you can make it back to where you were, Alheli, but there’s only one way to find out: Just do something — anything. Just get started; you have to start somewhere.

You don’t like where you are, but what the hell can you do about it now? You can sit around and wish you weren’t here or you can work toward *not* being here, not existing in this pathetic, weakened state. You’re going to recover either way. The question is: are you going to be the athlete you were – and know you still are – or will you use this as an excuse to ease off and ‘take things down a notch’?

Is that what you’re going to do, Alheli? Just give in?

No. That’s not who you are. You’ve come back before, you can do it again.

This didn’t defeat you and it won’t defeat you.

The first two weeks home I focused on stretching, on lengthening the tendons, ligaments, muscles that had all but lost their elasticity.

By the end of the second week I was able to not just stretch a split, but I could once again push into the over-split. I was able to fully stretch the quads, hamstrings, calves beyond their comfortable ranges. I could finally hold my shoulders back in a proper posture; that knot at my sternum became untied – I no longer felt perpetual suffocation.

This brief sense of accomplishment, of confidence, was shattered, however, the moment I moved back into (ridiculously) light weight work. Every muscle in my body had atrophied: my chiseled legs and arms were reduced to bony extensions; my abdominal muscles – that coveted 6 pack – was completely undefined, though sporting multiple new scars.

You have to start somewhere. Just do something.

So I did, and with every modified push-up, with every lift of a laughable dumbbell or barbell load, I fought the inner voice which screamed “this is such a waste of time. The lightest weight? Are you serious? That’s pathetic. You’re pathetic.”

I bought a top-of-the-line indoor cycle to begin rebuilding not only the cardio component, but to also start challenging the legs. The first attempt of cycling with any sort of tension had me spent in three minutes, so I rested, then did another minute. Rest, and another two, again, fighting that unforgiving, ruthless part of me that cannot – will not – accept less than 100%, all the time, no matter the circumstances.

30 minutes straight or it’s not worth it. Why are you resting? Harder, push harder. You’re wasting your time. You’ll never be what you were, where you were. Really – you’re going to settle for *that* effort? That’s sad, Alheli. Really, really sad.

It’s strange, though, to have, on the one hand, that unforgiving, unrelenting part of myself always asking for more, demanding I push harder, while, on the other side, fighting the anxiety and panic; Having another thought process entirely, saying, “No, you’re too weak. You’re going to pass out, going to have a heart attack.”

Always telling me, “You’re going to die.”

More than strange, it’s completely exhausting.

It was at the first follow-up appointment with my surgeon that I received the go-ahead to return to the gym.

“You cannot undo what’s been done surgically through your training,” my surgeon assured me. “Too often, when patients go home, they sit around, lay around, thinking rest will speed the recovery when, in fact, the opposite is true. They end up getting weaker, prolonging their recovery. Don’t be afraid to push the limits of what you can do. You’ll be fine.”

I was ecstatic — and terrified. Part of me wanted to hear permission to ease up, to ‘take it easy, go slowly,’ so that, maybe, I’d let up on myself.

But my surgeon didn’t give me that. He knows me, knows me physically, mentally, emotionally. Knows that, had he said anything else, I’d have been caught in the cycle of doubt. I’m a person who needs black or white. I need absolutes, or else I drive myself insane with ‘but’s, ‘could/should’s, and ‘what if’s.

He gave me that solid answer I needed, and I went to work.

Three short weeks after retuning home and barely a month out of intensive care, I ventured back to the gym.

I had my mother accompany me, as I was terrified of what might happen. Not that she could do much for me if my heart stopped or I collapsed, but at least she’d be there, and for whatever reason, there was a sense of comfort in that. She brought a book and settled herself in the lounge as I settled myself on the rower.

Forget speed, to hell with time, just get started. Start somewhere, do something.

I took it 500 meters at a time, though I did have a number in the back of my mind: 2k.

If I could row at least 2 kilometers, then I knew I could make it 3 the next time out. And once I hit that 3k, I’d know I could do the 5k — my pre-surgery (minimum) daily row.

The 500 meter mark passed, then 1 kilometer. By the 1500 m mark, I knew I’d reach that 2k goal with relative ease, so I resolved to do the full 5000 m; to row my 5k.

Just make it to 3, and you’ll have the 5. If you do 5 today, at your weakest, then you can do it any day.

It’s all a mental game with me: If I’d stopped at the 2k or 3k point, I’d doubt my ability to do the full 5k, even when (more) physically capable. So it was important to crush that doubt before it hit; to push my frail, exhausted body to its limit.

I don’t care how slow the pace, don’t care how long it takes. Just keep going, Alheli. Keep breathing, keep rowing. Come on. You can do this.

I could, and I did. It took me nearly 30 minutes (28:21, to be exact) of giving it my all, which was roughly 9 minutes slower than my pre-surgery, easy paced 5k row, but I made it.

And it felt incredible.

I followed the row with some assisted chin-ups and other standard upper body-weight exercises (various push-ups, dips, etc.) and some lighter kettle-bell work. It was fairly basic, beginner stuff, but after about 45 minutes, I had nothing more to give.

That wasn’t pretty, but you’re back, Alheli. And that’s all that matters

The first 4 weeks back at the gym were draining, not just physically, but also mentally, emotionally. There were days I’d quietly sob through training, struggle to get beyond the slight figure I’d glimpse in the mirrors; when I had to fight the urge to say “to hell with it all” and never return.

Everything was exhausting; nothing felt right.

People who’d approached me to compete for their given organization (rowing, physique/fitness, triathlon, to name a few) before my surgery now struggled not to stare. One fellow gym goer who’d always comment on my “incredible legs” approached me, asking if I had a sister “who used to come here, I haven’t seen her for a while. But you two really look alike.”

The owner of the gym, with whom I have a great relationship, demanded to know “what are you doing (to myself)?” followed by a bulimic gesture. I sat him down and explained what had happened, and, visibly embarrassed, he apologized.

I didn’t blame him and don’t hold it against him, though I wish he’d have just asked questions rather than made accusations/assumptions.

What little confidence I had in rebuilding seemed to be challenged by something, by someone, at every turn.

You can’t control what others think, you can only control how you react. Have patience, keep pushing.

I was soon back to 5 days per week at the gym, each day rowing 5k followed by weight work. Every couple of days I shave another dozen or so seconds off the first-day-back 5k time, every week I extend the length of the weight sessions, eventually hitting my usual 90 minutes, would increase the load of the weights used. And after 10 weeks or so, I finally began to see results.

Others did, too.

Trainers, colleagues – even the person who’d asked if I had a sister – approached me, noting the “incredible amount of muscle you’ve packed back on,” complimenting my “remarkable, unequalled work ethic.”

“No one could do what you’ve done,” said one industry stalwart.

A nice confidence boost, to be sure, but I was hardly back to my pre-surgical state — not even close, in fact. But things had finally started to turn, to head in the right direction, and the body finally appeared to respond to the efforts I put forth. The small accomplishments began to add up: I no longer doubted my ability to fully recover – I just had to have the patience.

Though the physical recovery was moving along nicely, the emotional recovery hit a snag. I’d been warned of a “serious, post-operative period of depression (read: trauma)” that often accompanies major, invasive procedures and life-threatening experiences, but I was certain that, given the wide range of coping strategies developed during/after the tumultuous childhood years, I’d be able to tackle any supposed depression without issue, should it even hit.

Well, it did hit, and it hit hard. What began as a general sense unsettledness after roughly one month of being home had developed into deep despondency by two.

It wasn’t so much depression in the classic sense; it was more of a deep, simmering anger, bordering on rage. Everything bothered me, everyone irritated me. I didn’t want to be around anyone, least of all myself. I stopped taking calls, stopped replying to emails, didn’t return messages. There were days I wanted nothing more than to erase myself from the internet; Just close all my accounts, disappear, and cut ties with everybody.

Things began to lose meaning. Even at the gym, I found I was forcing myself through the motions. There was no enjoyment, no satisfaction. Just routine.

I became unnecessarily aggressive, needlessly bitchy, on social media and privately apologized to a number of people who’d noticed a shift in tone.

This is just part of the process, I’d tell myself. This isn’t going to be forever. Just keep forcing it, keep going through those motions, no matter how empty they feel. No matter how hollow life seems at the moment, it’s not all for naught. You’ll see. Just keep pushing.

As I neared the three-months-at-home milestone, the darkness began to lift. I no longer questioned why I’d fought so hard to survive; no longer wondered if, maybe, it would have been better – for everyone – if I hadn’t.

That thought crossed my mind more than I care to admit.

I was able to find joy in little things again, able to read for the pleasure of reading, watch a movie without the guilt of ‘wasting time.’

Wasting time. Right. Because you have other pressing, super-important things to do? Adorable, Alheli.

I started to communicate again, with everybody; Even considered venturing out, being *gasp* a normal, social being.

And on October 2, my 29th birthday, I did.

I met two wonderful women for lunch, and I thoroughly enjoyed myself. I thought I’d be anxious, would want to bail early, to just get home and be alone, but I didn’t. I felt back to my old, sociable self, and it was wonderful.

Later that afternoon, however, I was reminded that things remain far from normal.

I’d taken Brio to the park for a run – it was a beautiful day, and though technically a ‘rest’ day (off the gym), I felt buoyed from the birthday lunch. It wasn’t long after Brio and I had set off on the trail that I felt a terrible pain in my abdomen.

It’s psychosomatic, I thought. This is just a manifestation of anxiety — you didn’t feel it at the time, but the lunch was probably more stressful than you thought. You’re fine, keep going.

But I wasn’t fine. In fact, I was now doubled-over, unable to stand straight, on the verge of passing out from the pain.

Maybe your guts are having a spasm from sitting too long on the hard seats at the restaurant; that’s probably why your back is hurting too. Just focus on getting back to the car. Once you sit down, this will stop. It’s just a spasm. You’re fine.

I stumbled my way back to the car, loaded Brio and sped home, where I collapsed.

Fortunately, my mother arrived from work just minutes later, and she rushed me to the ER.

My obvious distress prompted the triage nurse to take me directly to the back, and after taking my vitals – my pulse was an incredibly low 37 – I was bumped to the front of the line. I was immediately sent for a set of abdominal X-rays, and the results seemed to confirm the doctor’s suspicion of a small bowel obstruction (SBO). I was then slated for a CT scan, and began the timed intake (drinking) of the 2 liters of contrast fluid which would illuminate my intestine.

Normally it isn’t advisable to ingest anything with an obstruction, but having just recovered from renal (kidney) failure caused by the injectable contrast back in June, it was determined the oral route was the better option.

Over the course of 90 minutes I sipped at the mixture, the pain under control thanks to a steady stream of morphine into my IV, and a few hours after arriving at the ER, the CT was complete and the SBO diagnosis confirmed.

I was formally admitted, though a bed would’t be ready until (later that) morning, so I was sent to a more private, sort of holding area which, oddly enough, was the same room in which I spent the night upon readmission following the first (May 13) surgery.

And it’s again in that room that I had the NG tube inserted to drain the contents of my stomach, to prevent anything else from reaching the small intestine, thus providing a ‘rest’ for the gut.

Now, when an NG tube is inserted it’s almost guaranteed the patient will vomit. I knew what was coming, had this done multiple times before, but what I expelled that night horrified me: It was blood. Bright red, and fresh, and lots of it.

I turned to the nurses, hoping for a sense a reassurance, but they seemed just as troubled by the sight. They quietly conferred with each other before slipping from the room to consult the surgeon on call. There was a possibility the blood was caused by the first, failed attempt to insert the NG; perhaps something in my nose or throat had been cut, maybe a vessel punctured, because the blood was so fresh.

I assume this was the case, as no further investigations were pursued, and after about an hour, the contents being evacuated by the NG were no longer tinged red.

I was eventually admitted back to unit 83 where I was greeted with love and warmth from the bevy of nurses who’d cared for me throughout May and June. Though sad to see me back under the circumstances, they seemed relieved to see I no longer looked on the verge of death. That, save for this little roadblock, my recovery was progressing well.

“This is a minor setback,” one nurse told me. “Not even a setback, more of a delay. These things happen, it’s all part of the process. We can get you out of here without another surgery, I’m sure of it.”

It wasn’t long before my surgeon, who I’d met with for a second follow-up just weeks earlier, came to see me.

“When I said we’d be ‘joined at the hip for the next little while,’ I didn’t mean for you to prove me right, or at least not this soon,” he quipped. “Lets fast-track this, shall we?”

He wanted to get the obstruction resolved without further intestinal resection. I was already dealing with short-bowel syndrome – a malabsorption disorder caused by damage to the small intestine, now exacerbated by the removal of segments of the small gut back in May and again in June – which has made regaining the weight lost that much more of a challenge.

I could not – cannot – afford to lose more healthy intestine. I no longer have a large intestine, which is fine, you can live without your colon, but you cannot survive without the small intestine.

I desperately need to hang on to every inch I have left.

For another 24 hours, the NG tube kept my stomach – and by extension, my intestines – completely empty, draining it of even the natural gastric juices produced, saliva swallowed. Various compounds were put through the IV to help bring the intestinal inflammation down, to kill the pain, and to dull the nausea.

The room I’d been placed in was quite isolated, located in a far corner of the unit, and was quiet, so incredibly peaceful. My room overlooked the Glenmore reservoir, and as I drifted in and out of sleep, I’d catch glimpses of competitive rowers out on the water.

There’s a certain meditative quality to rowing; it’s physically exhausting, yes, but the repetitive nature evokes a sense of calm for me, and seeing the rowers out on the water brought about that same comfort.

The next morning my stoma (the small portion of exposed intestine) was pouring out both fluid and gas – two important signs that the obstruction had begun to disperse. A follow-up scan confirmed the total blockage was now partial, and that I’d likely escape with my intestine intact.

Rather than remain in hospital for another week, however, my surgeon suggested I’d do just as well at home, so long as I strictly adhere to the plan, which would ensure the obstruction would fully rectify: A complete liquid diet for 24 hours, followed by mashed/pureed food for an additional three days.

“Imagine trying to jam an apple through a straw, it’s not going to work.” My surgeon explained. “Your intestines are swollen and inflamed, and there are segments that are incredibly narrowed. Further, there is scar tissue that has yet to work itself out from your earlier surgeries. If you go home and you push the diet, you’re going to end up back here. I’d suggest you consider putting all your fruits and veggies through a blender for the foreseeable future; not only will it make nutrient absorption easier, but it will take away the constant threat of obstruction you’re going to live with. It’s just the way your guts are.”

Ever since the intestinal rehab, I’ve followed the diet set out by my gastroenterologist, and followed it religiously. Not only did it give me peace of mind that I was doing what’s best for my gut, but if/when something went wrong, I could take comfort in knowing that it wasn’t anything that I did, or rather, that I failed to do.

Or, if I strayed from the plan and something happened (like this obstruction experience – I pushed the diet too far, too soon), I could pinpoint where I went wrong and learn from my mistakes.

When my gut was entirely non-functional and people accused me of relapsing into an eating disorder or otherwise, somehow, ‘doing it to myself,’ I swore that when things were finally fixed, when my gut was healthy again, I’d make a point of doing everything exactly by-the-book.

True, people will always create their own reality, come up with their own explanations/version of events, but I refused to ever again be put in the position of taking blame, of being accused of contributing to/causing what is ultimately an unfortunate roll of the genetic dice.

Yes, I’d been hopeful that I could return to some sort of ‘normal’ way of eating following the final surgery(ies), that I’d no longer have to adhere to the “what my GI team tells me to eat” diet, but in the end, if that’s what will keep my intestines functioning and my body healthy, then it’s a sacrifice I’m more than willing to make.

And, as noted above, if/when something goes wrong, I can take comfort in knowing that I’ve done everything right, followed through with all that was asked of me, so that I won’t blame myself, even if, even when, others do.

And they do, believe it or not. I still have otherwise intelligent, well-meaning people in my life who insist my having had an eating disorder during childhood somehow caused/contributed to the development of ulcerative colitis (UC). Something that, quite obviously, is neither true, nor possible.

Tellingly, these people also tend to get angry when I follow my doctors’ advice, directives to the nth degree.

These folks always seem to know better than my medical professionals.

I don’t blame them for their ignorance, nor do I hold it against them. Everything I’ve been through, both in childhood and in recent years, has affected everyone, and has been hard for everybody. But I do find it sad that, still, some people are either unable or unwilling to get past that stigma. I’ve learned to accept that I cannot – nor should I waste time trying to – change the faulty assumptions/beliefs others cling to regarding my life/my experiences.

It’s their issue, not mine.

Like water off a duck’s back.

But I digress.

The first few days home from the hospital following the obstruction were a challenge: the intestine was on the mend but was still incredibly inflamed and distended. My usual outlet for stress – physical activity – was out of the question, as even light walking produced too much abdominal pressure. But, as was promised, the swelling lessened with each passing day, as did the pain and the nausea.

On the fourth day home, I was able to increase my caloric intake, start re-advancing the diet, so I felt comfortable re-introducing light physical activity. I returned to the park where the obstruction hit, planning to take Brio for a nice long walk.

As I pulled into the parking lot, however, I was overcome by anxiety. I parked the car and proceeded to have a full-blown panic attack. I sat trembling, sobbing, and trying to make sense of what was happening.

What the fuck is wrong with you? Just get out and walk!

But I couldn’t. My mind raced with various worst-case scenarios: Remember, your pulse was dangerously weak just days ago. Your heart’s going to stop. How do you know the obstruction isn’t sitting there, just waiting to hit again? Your intestine is going to rupture. You’re going to get dizzy and pass out. Your diet has been too lacking, you’re too weak.

After about 20 minutes I was drenched in sweat and mentally exhausted, but I refused to leave without taking Brio for a walk, without overcoming that anxiety, dealing with that, for lack of a better term, trauma.

I forced myself from the car, summoned Brio, and off we went. I recited song lyrics to keep my mind occupied, to prevent its straying back into panic territory. I clutched Brio’s leash tight enough that I thought it might fuse to my hand, and before I knew it we’d made our way around the perimeter of the park — twice.

It’s all part of the process. Just keep going.

The next day, feeling a renewed sense of confidence, I decided to return to the gym. Not for a full workout, mind you, but to get started; to do something. Because there was a fear surrounding that, too.

There was no parking lot panic attack, though I did have a brief anxiety attack in the change room before starting. I forced myself to execute the full 5k row (which, oddly enough, was one of my faster post-surgery times: 22:13), repeating “You’re fine” with seemingly every stroke. I followed the row with a shortened weight set, again reassuring myself “You’re OK” with every set, every rep.

It took another two weeks to start feeling somewhat normal again, for the obstruction to fully resolve and the weight to re-stabilize. When literally every calorie counts, missing even one meal or snack – or the gut being too swollen to absorb everything taken in – quickly takes its toll.

But I’m once again settling into a routine, trying to balance the physical rebuilding with required rest/recovery time; experimenting with the diet, trying to challenge the intestines without entering obstruction territory; challenging the mind and satisfying the appetite for knowledge through reading, writing, and research, but learning to accept that some days the concentration just isn’t there. Some days, the body and mind are simply exhausted, and that’s OK.

I’m learning to relax, and to be OK with relaxing; learning to give myself permission to be still, and sometimes, to be unproductive. Because those days will happen, but they’ll eventually wane, and in time, become rare.

It remains difficult to focus on the long-term when the day-to-day remains turbulent, but I refuse to avert my gaze from that end point: 18 months, I’m told, and I’ll have crossed the finish line I’ve been perusing for nearly a decade.

I’m just shy of the 4 month mark; I’ve now been home for 114 days.

There is one outstanding matter, though. I expect to hear soon about whether the second, final medical bill which continues to climb — presently at $70,000 (no, that’s not a typo) — will be covered or if I’ll have to take out another medical loan. Given that the treatment was medically necessary – and urgent – for something directly related to the prolonged non-functioning gut, I’m holding out hope.

What’s important, I suppose, is that I’m alive; that I cleared the final hurdle and, though I’ll likely experience a few more stumbles before crossing the finish, I no longer question my ability to reach it.

I look forward to the life that awaits on the other side of that line.